Press Release: The Singapore Association for the Deaf signs MOU with Grab to empower the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community

- SADeaf appoints Grab as SADeaf’s Ambassador, a testament to Grab’s contribution to the community.

- Highlights of partnership includes Grab providing SADeaf beneficiaries access to new economic opportunities and SADeaf providing skills upgrading access for existing Deaf Grab driver and delivery-partners.

Singapore, Friday, 27 September 2019 —The Singapore Association for the Deaf (SADeaf) today signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Grab to appoint Grab as SADeaf’s Ambassador to form a partnership to promote Deaf awareness and make the Grab platform more accessible and inclusive for the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community. Highlights of the partnership includes a public education campaign and Grab in-app feature enhancements to promote better communications between the public and Deaf partners, as well as skills upgrading opportunities for Grab Deaf partners. The partnership is also one of the many initiatives under Grab’s ‘Grab for Good’ social impact programme which aims to empower people in Singapore to benefit from the fast-growing digital economy and have more choices and opportunities to improve their livelihoods.

The MOU was signed by Ms Judy Lim, Acting Executive Director for The Singapore Association for the Deaf and Mr Yee Wee Tang, Country Head of Grab Singapore, and witnessed by Mr David Phung, Head of Corporate Affairs, The Singapore Association for the Deaf and Mr Russell Cohen, VP for Regional Operations, Grab at an appreciation luncheon hosted by Grab for its Deaf and hard-of-hearing driver and delivery partners today. Grab was also appointed as SADeaf’s Ambassador for the Deaf, a partnership between SADeaf and corporates that fosters ongoing support and collaboration for the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community, at the same event.

“Grab believes everyone should have access to financial independence – regardless of background or ability. Through this partnership, we hope to empower more Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals by providing them with another source of income. Beyond that, we also hope to gain more understanding of their challenges and offer a friendlier environment for them to work in,” said Yee Wee Tang, Country Head of Grab Singapore. “We’re committed to inclusivity, and want to support these partners as they create a better future for themselves and their families. They inspire us every day, and it motivates us to continually design and build more products to enable more meaningful earning opportunities.”

Ms Judy Lim, Acting Executive Director for The Singapore Association for the Deaf, said “We are very happy with this collaboration with Grab becoming our Ambassador for the Deaf. It has brought about employment for Deaf and hard-of-hearing drivers, creating independent living and financial sustainability for them. This has also been made possible through the use of Grab app where there is no need for verbal communication between the driver and the passenger. Passengers who take the ride with Deaf drivers are also being notified by the Grab app. There is even the dashboard at the back of the seat to tell you how to communicate with the Deaf. This makes the ride very friendly and comfortable, helping passengers gain a better understanding about the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community. We appreciate Grab for this very meaningful initiative.”

Today, some 50 Deaf driver and delivery-partners are earning an income on the Grab platform in Singapore. The year-long partnership will allow Grab to better understand the needs and challenges of the local Deaf community, which will be used to build solutions and advocacy programs to serve them better.

It also serves to further strengthen the commitment towards specific initiatives that can best provide income and welfare opportunities for the Deaf driver and delivery-partners. Both parties are collaborating to provide the following support:

- Providing access to new economic opportunities. For Grab to facilitate SADeaf beneficiaries who are keen to be driver and delivery-partners on the Grab platform. In an industry-first move, Grab will also reduce the commission rates (contributed to the platform for every ride) by 50% through a rebate scheme for existing and new Deaf drivers who are members of SADeaf.

- Providing access to new economic opportunities. Grab will facilitate the onboarding process for SADeaf beneficiaries who are keen to be driver and delivery-partners on the Grab platform.

- Promoting skills upgrading. SADeaf will provide skills upgrading access through existing programmes for existing Deaf Grab drivers and delivery-partners.

Members from the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community are encouraged to sign up as a member with SADeaf to take full advantage of the benefits.

As part of its commitment to do more for the community, Grab had earlier conducted focus group discussions with its existing Deaf driver-partners to get their feedback on how Grab can provide them with a better driving and delivery experience. Based on their inputs, Grab will be implementing the following product, platform and process improvements in the coming year:

- Customised Feature Support on Grab

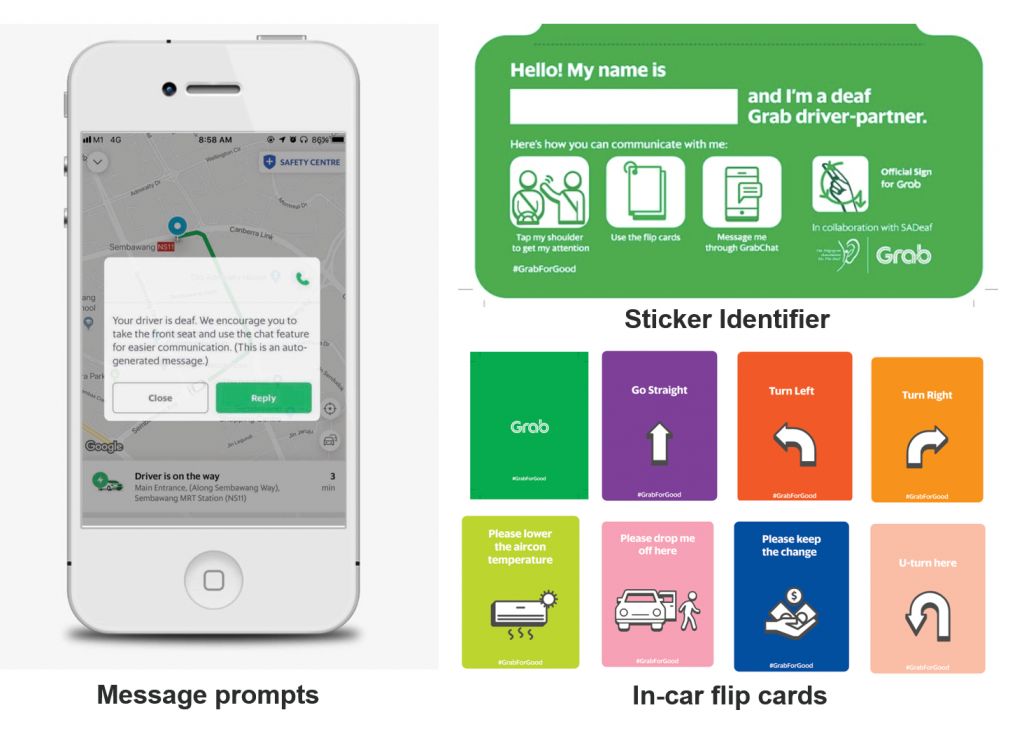

- Message prompts to passengers and customers informing them that they have been paired with a Deaf partner, advising them to use the GrabChat feature to communicate.

- Turning off the call function for Deaf and hard-of-hearing driver-partners. This is to prevent passengers from attempting to call their driver-partners and to communicate via GrabChat feature instead.

- Sticker Identifier attached to the driver’s headrest to inform passengers on the right way to communicate with their drivers.

- In-car flip cards to further facilitate better non-verbal communication between our driver partners and passengers, covering typical requests and concerns such as directions, air-con temperature, toll fee exclusion in fare. For GrabFood delivery-partners, a set of visuals have been developed to allow easy access through the Grab delivery-partners’ mobile phone.

- In-app communication guides on how to interact with Deaf driver-partners

- Enhanced training and onboarding materials with local subtitles and sign language to ensure smoother registration for Deaf partners.

- A public education campaign to promote better communication and empathy between partners and passengers, address misperceptions and raise confidence in the Deaf driver-partners’ abilities to do their job. This includes educational videos on hand signs so the public can learn to communicate with the Deaf community.

Teo Hang Keong, a Grab Deaf driver-partner in Singapore, said, “I have a full time job as an intelligence data analyst, but it is not enough to support my family. Driving part-time for Grab to supplement my income has been helpful, as I am also planning for my retirement.”

When asked about his experience as a Grab driver-partner, he shared “The passengers I come across are very understanding, and they do not doubt my driving skills just because I am Deaf. Some of them are even able to communicate with me using sign language, which really makes my day!”

Peter Ho, another Deaf-driver partner in Singapore, shared, “I have been driving since I was in my 20s. My dad told me to get a driving license as driving is a useful skill that would come in useful in the future. I like driving because I get to meet and interact with new people from different parts of the society. I also hope they gain an understanding and patience with people with disabilities.

I enjoy sending them to Changi Airport, and helping them with their luggage. While driving can be tiring at times, my sons know that I do it for them and that’s what keeps me going.”

About Grab

Grab is the leading super app in Southeast Asia, providing everyday services that matter most to consumers. Today, the Grab app has been downloaded onto over 152 million mobile devices, giving users access to over 9 million drivers, merchants and agents. Grab has the region’s largest land transportation fleet and has completed over 3 billion rides since its founding in 2012. Grab offers the widest range of on-demand transport services in the region, in addition to food and package delivery services, across 339 cities in eight countries. For more information, please visit grab.com.

About SADeaf

Established in 1955, the Singapore Association for the Deaf (SADeaf) has been serving the Deaf and Hard-of-hearing community for the past six decades. SADeaf is a member of the National Council of Social Service (NCSS), and is supported by Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) and Ministry of Education (MOE).

The association is also affiliated, internationally, to the World Federation of the Deaf (WFD) and, locally, to the Children Charities’ Association (CCA). SADeaf will be celebrating its 65th Anniversary in 2020. For more information, please visit saDeaf.org.sg

| Media Contact Mr David Phung, Head of Corporate Affairs, SADeaf, david@sadeaf.org.sg, 9105 5048 |

Former Patron Mrs S R Nathan receives Honorary Posthumous IRO Award on behalf of her husband

The Singapore Association for the Deaf (SADeaf) congratulates our former Patron Mrs S R Nathan on receiving the Honorary Posthumous IRO Award on behalf of her husband – the late President of Singapore Mr S R Nathan. Mrs Nathan, who was SADeaf’s Patron from 2000 – 2013, accepted the award from Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at a gala dinner to commemorate the IRO’s 70th anniversary. The award honours Mr Nathan’s commitment in promoting the cause of inter-religious cohesion and harmony.

Photo: Courtesy of Straits Times

First Deaf Recipient of the Public Service Medal (Posthumous)

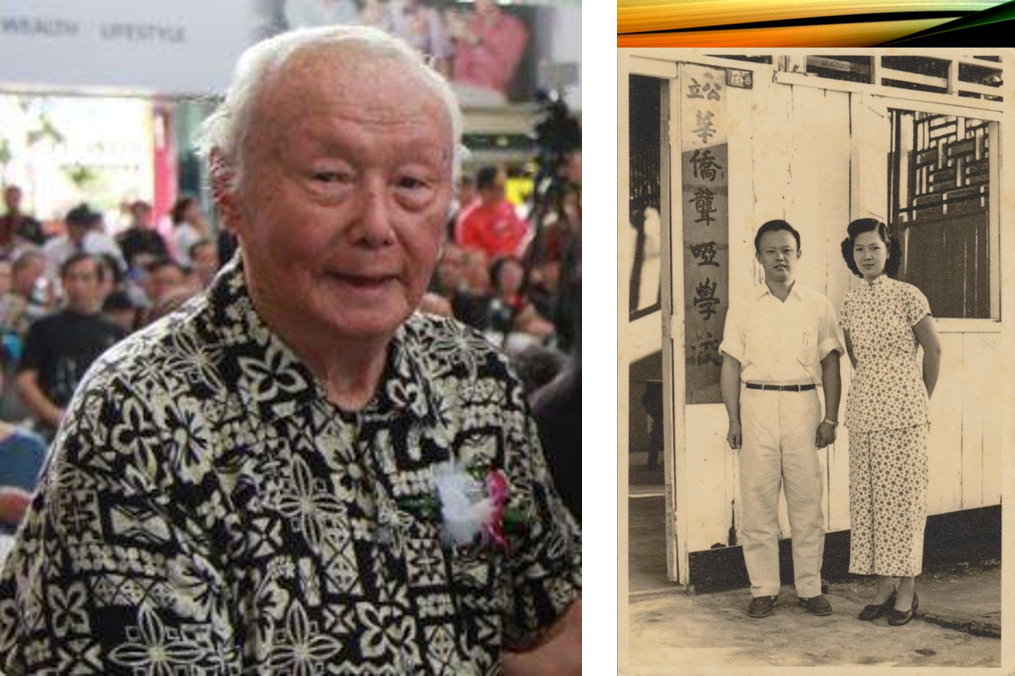

The Singapore Association for the Deaf is proud to announce Mr Peng Tsu Ying (92), the late former trustee of the Association will be receiving the highly-honoured Public Service Medal (Posthumous) at the National Day Awards in 2019 for his selfless dedication to Deaf education for decades.

About Mr Mr Peng Tsu Ying

Mr Peng, who passed away in October last year, lost his hearing at the age of five after taking too much medicine for a high fever. After receiving education for the Deaf in Hong Kong and Shanghai, he came to Singapore in 1948 to help his father in his business. When he arrived, he realised that Singapore did not have a Deaf school and he decided to establish one, so that the Deaf can have access to education.

However, the colonial government then only approved him to run a school at his home. He then started his private school in 1951, initially with only nine students. With the help of his reporter friends, Mr Peng published articles in two Chinese newspapers to advertise his school and raised $5000. In 1954, he established the Singapore Chinese Sign School for the Deaf at Charlton Road in 1954, using Shanghainese Sign Language as the medium of instruction.

The school merged with the Oral School for the Deaf, established by the Singapore Red Cross, in 1963 to form the Singapore School for the Deaf. Mr Peng was one of its founding Principals and led the school’s Chinese Sign Language department.

Besides dedicating his life to Deaf education, Mr Peng was also an outstanding motor racer. From 1959 to 1967, he won 36 trophies in the local motorsport races with his Lotus open-top sports car. In a media interview after a race in 1975, he said that he took part in motorsports to prove that “being deaf is no handicap in being skillful.”

Mr Peng is survived by three children, seven grandchildren and three great grandchildren.

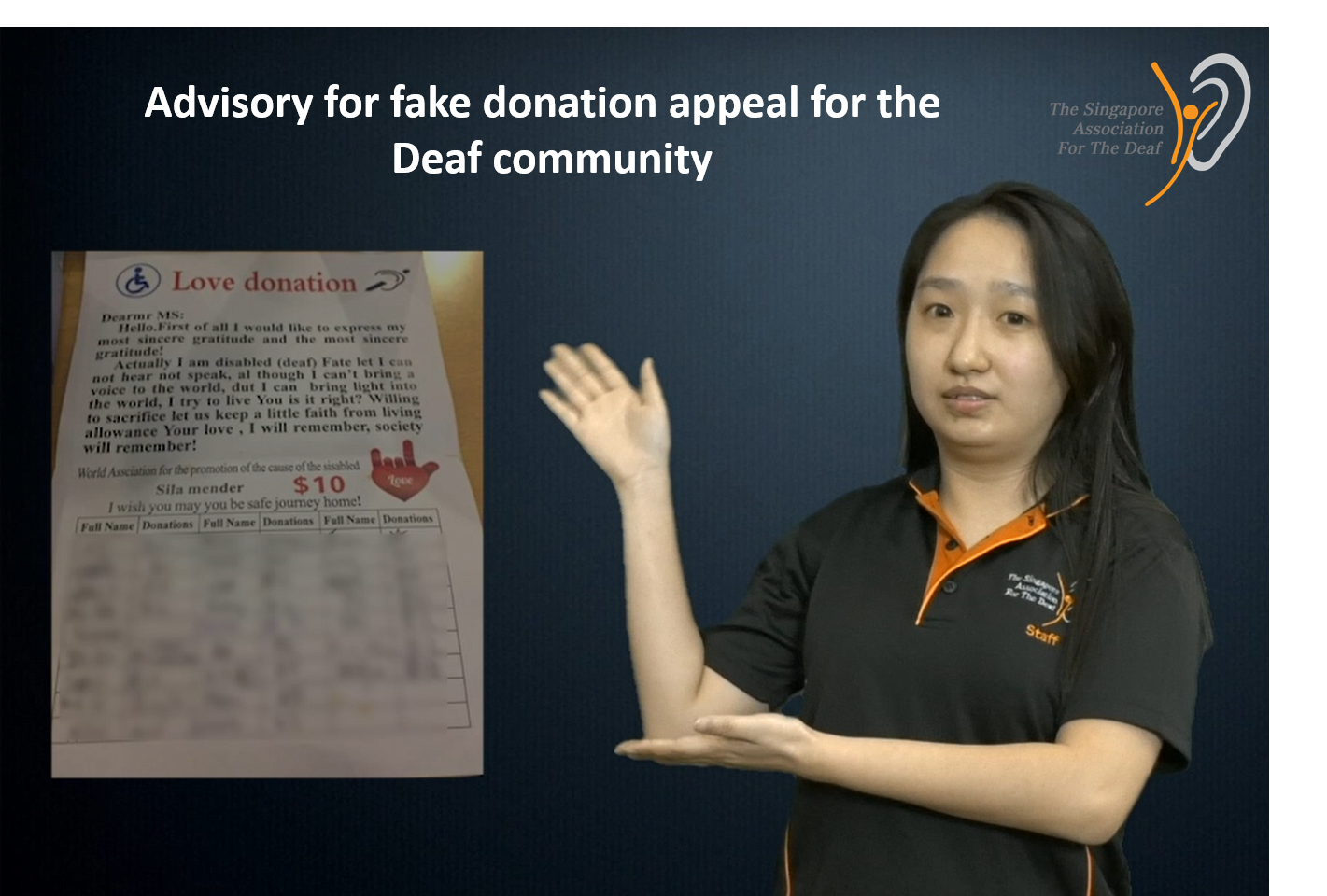

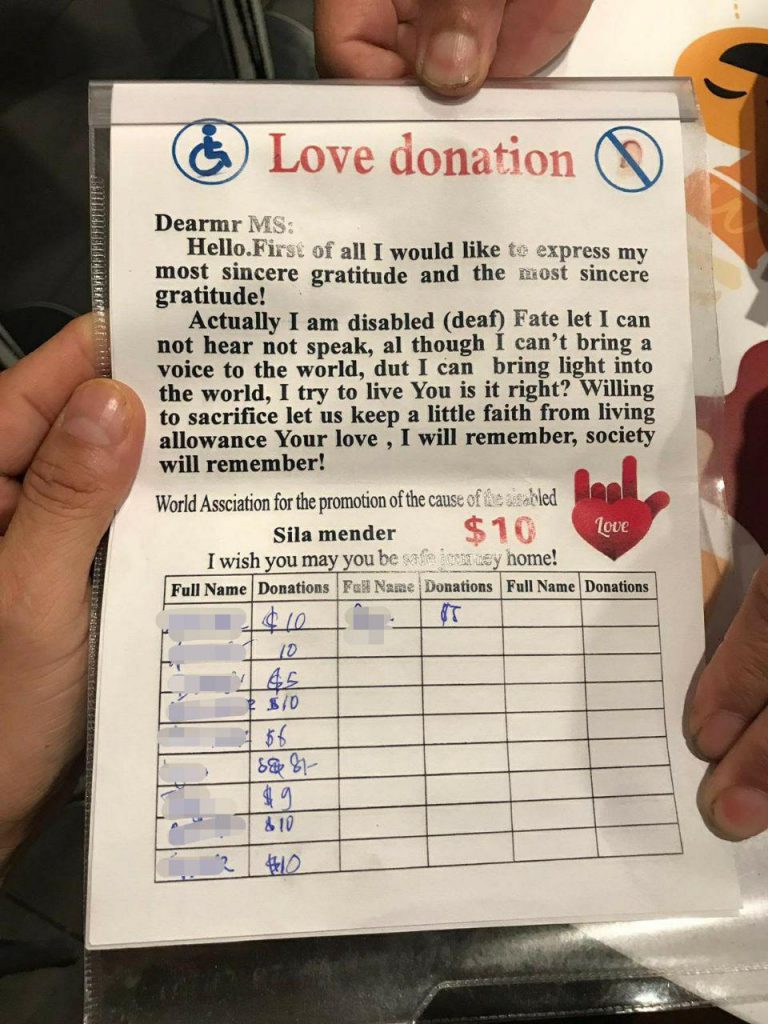

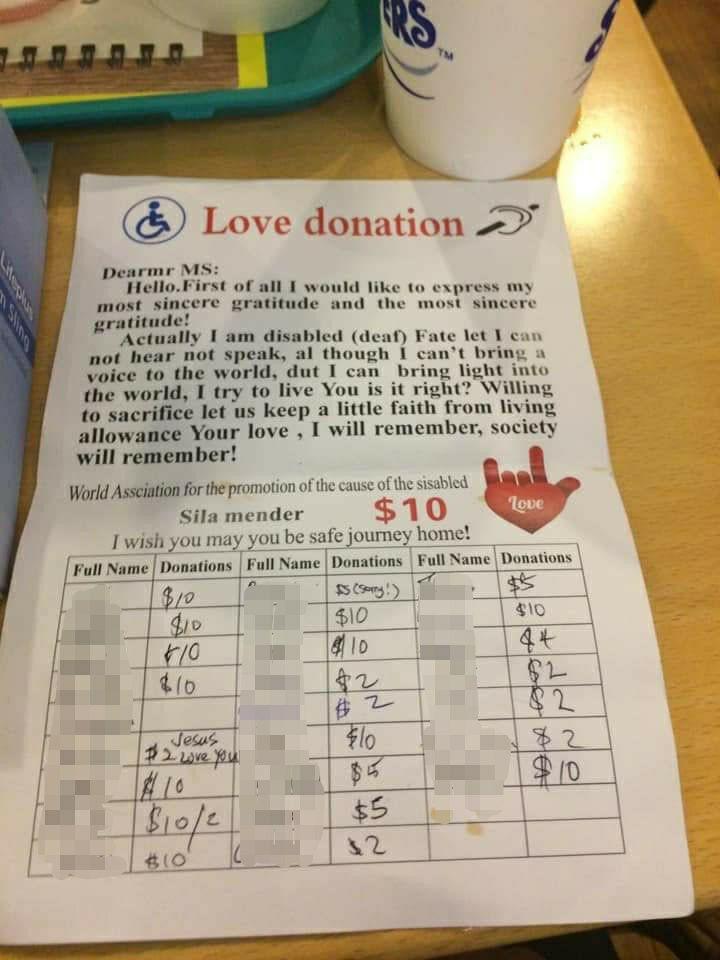

ADVISORY ON FRAUDULENT DONATION APPEAL FOR THE DEAF COMMUNITY

Members of the public are advised to ignore or report to the police should you be approached for donation to the Deaf community by unauthorised agents. An image of a fraudulent donation card is provided below this advisory for your reference. Please do not respond to such donation requests. We also encourage donors and the public to practise “Ask. Check. Give.” before donating.

Ask before giving.

- Who is the beneficiary?

- What will my donations be used for?

- How can I receive updates?

Check the fund-raiser’s legitimacy and terms and conditions.

- Scan the QR code on the fund-raising permit;

- SMS to 79777; or

- Visit the Charity Portal and search for the charity name.

Give with peace of mind.

Together, we can build a trusted and thriving charity sector. For more information on Safer Giving, check out the Charity Portal here.

‘Why take on the extra burden?’: Parents with disabilities tackle misconceptions about raising their own families

When Mdm Neo discovered that both of her children were deaf, like her and her husband, she took it in stride. “It didn’t matter that they were deaf,” signed the 69-year-old via interpreters from the Singapore Association of the Deaf.

“I was just worried about their education … I wasn’t sure how to teach them and had to send them to a school (for the deaf) to make sure they received proper education.”

Mdm Neo, who grew up with five other siblings who were also deaf, said her disability never deterred her from her role as a mother.

“I just wanted to look after my kids,” she said simply.

Find out more at

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/parents-with-disabilities-tackle-misconceptions-raising-families-11729976?cid=fbcna

22-year-old Vanessa Chea says her hearing loss doesn’t make her different

SINGAPORE: When Ms Vanessa Chea sat for an exam in Temasek Polytechnic where she studied till a year ago, a lecturer asked if she needed extra time to complete the paper.

It was tempting for her to grab the advantage, but Ms Chea who is hard of hearing, declined.

“I just see myself like anybody else,” she told CNA.

Her hearing difficulties do not affect her ability to think, something she feels not everyone knows.

“I noticed that people tend to associate hearing loss with intellectual disability,” she said.

People also tend to think they needed to shout if someone cannot hear well, but this just hampers her ability to lip-read, she said.

While she has mastered lip-reading, she said: “When you shout, the lip shape is very different from what you are saying, and that makes reading very difficult.”

Even if they do not have such misconceptions, they may not empathise with her condition.

Ms Chea recalled having a lecturer who refused to use a device that would help her hear better in class.

“She found that it is not a good thing for me to depend too much on technology,” she said.

Ms Chea ended up not being able to follow her lessons.

She has also had peers take advantage of her hearing loss to claim credit for her work, Ms Chea said.

CUTTING THROUGH THE NOISE

Her struggles fade into the background when she is looking through the lens of a camera.

Born the middle child to avid photographer parents, Ms Chea initially did not like the hobby.

“I thought it was all about just pressing the shutter button and the picture coming out,” she said

But her view changed after attending a workshop with a professional landscape and nature photographer who displayed photos taken in scenic New Zealand.

Then 14 years old and a member of the Digital Media Club at Saint Anthony’s Canossian Secondary, she started appreciating the hobby.

“When I started taking photos, I realised that the process of taking photos is quite challenging and tiring, because not only do you need to have a keen eye for it, you also need to learn to be fully prepared for whatever weather conditions,” she said.

FROM NOT LIKING PHOTOGRAPHY TO WINNING AWARDS

She focused on mastering the techniques and started reaping the rewards soon enough. Ms Chea won the first time she entered a photography competition. She realised that the outcome could be different if she had not rushed from her class and arrived in time to an interview for shortlisted participants.

“So can you imagine how close I was to not getting the prize?” she asked.

The photos she submitted made it to a display at the National Museum, she said with pride.

The win was no fluke. She won in another photo competition, this time with pictures taken at the Supertree Grove at Gardens By The Bay, her favourite spot.

“I prefer to take photos where there are not much people around, because it allows me to appreciate the nature, have some quiet time on my own,” she said animatedly.

Ms Chea has taken some risks to get the perfect shot. Once, she slipped on a rock, and another time, she stood undeterred as thunder rumbled and lightning flashed while others were scrambling for shelter.

“Afterwards it poured. It was challenging. But when I see the photo, I am proud of it,” she said.

Her family used to worry because she would often visit remote places to take photos.

“They worry that with my hearing loss, I would not be aware of the dangers around me,” But Ms Chea’s other senses are heightened, and she is more careful to make up for what she cannot hear, she said.

She also suffers a little for her art, getting back pain from walking around with her DSLR hanging from her neck, and blisters on her feet.

It was a relief then when she managed to get funding for a new, lighter camera through the Mediacorp Enable Fund. A social worker at Temasek Polytechnic had suggested that she apply for it.

“My family is financially stable, but I find it painful to see my parents spend so much money for my education, my hearing needs, and I just don’t want to trouble them further. I don’t want to be a financial burden, so I decided to apply,” she said.

She added that in photography, having the right equipment is very important.

“Having the right gear and equipment will allow me to achieve my vision better,” she said.

DON’T BE AFRAID TO TRY NEW THINGS

Things are looking up for Ms Chea in other areas as well.

Having undergone a cochlear implant earlier this year, she hears much better now.

She will also be starting university education this month, after having to postpone it due to her hearing problems.

Having once been someone who was not confident enough to try new things, Ms Chea had advice for anyone who might feel uninspired: “Time waits for no man, so don’t be too afraid of trying new things. Trying something out of your comfort zone is a good thing.”

Ms Chea is a beneficiary of the Mediacorp Enable Fund (MEF), a charity fund by Mediacorp and SG Enable that aims to build a society where persons with disabilities are recognised for their abilities and lead full and socially integrated lives. Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong is its patron.

Source: CNA/ja

Read more at https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/i-just-see-myself-like-anybody-else-22-year-old-vanessa-chea-11789938

Art started as a refuge to cope with deafness for award winner but led to stellar career

By LAUREN ONG

Extracted from TODAY dated 8th July 2019

SINGAPORE — When Ms Chen Ziyue was in school, she sought comfort in the world of art whenever she was having a hard time.

Given her profound deafness, she struggled to communicate with her peers, because of her poor speech clarity and lack of exposure to sign language back then.

“I became drawn to art as it allowed me to express myself freely and to forget about my struggles and frustration with my deafness,” she told TODAY.

On Wednesday (July 3), Ms Chen, 33, received a S$5,000 award at the Istana at the Goh Chok Tong Enable Awards, which are designed to foster a kinder, gentler and more inclusive Singapore.

Art may have provided solace in Ms Chen’s early life, but it eventually led to a career path — and a distinguished one at that, as an illustrator of children’s books in Singapore and abroad.

Some of her clients have included the Ministry of Education, Singapore publisher Epigram Books, consumer technology publication HWM Magazine and global publishers Random House as well as Simon and Schuster.

Ms Chen illustrated the cover of The Bad Kid written by Sarah Lariviere and published by Simon and Schuster. Illustration: ziyuenchen.com

Ms Chen completed her studies at the Ringling College of Art and Design in Florida in the United States in 2013, under a scholarship from the Media Development Authority (a precursor to the Infocomm Media Development Authority) before launching her stellar career.

“I later learnt that I could connect with people through art and knew that it was what I wanted to do, eventually creating illustrations for children’s books. I’ve intended to illustrate my personal story to share my learning journey and have it published someday,” she said.

Ms Chen was one of the 10 recipients of the UBS Promise Award at the Goh Chok Tong Enable Awards given out by Emeritus Senior Minister (ESM) Goh Chok Tong and President Halimah Yacob. The awards are an initiative under the Mediacorp Enable Fund, a charity for people with disabilities, that grew out of the TODAY Enable Fund.

The awards recognised a total of 13 people with disabilities for their achievements and potential in their respective fields.

Ms Ku Geok Boon, chief executive officer of SG Enable, the fund administrator for Mediacorp Enable Fund, said that the recipients of the awards sent “a strong message that persons with disabilities have ambitions and goals, and the determination and courage to achieve them’’.

“These awards, we hope, will be a catalyst for Singaporeans to look at persons with disabilities in an even more positive light and come forward to support their endeavours,” she said.

In a speech at the event, President Halimah highlighted the Government’s push towards a more “caring and inclusive society” through the third Enabling Masterplan, a five-year roadmap that was unveiled in late 2016.

THOSE WITH DISABILITIES ‘MAKE SIGNIFICANT CONTRIBUTIONS’

“The Government is actively engaging persons with disabilities and their caregivers to better understand their aspirations, needs and challenges.

“The Government is also working with social service agencies and tripartite partners to improve education, training and job placement for persons with disabilities, and identify suitable employment opportunities for them,” she said.

President Halimah also emphasised the importance of recognising the capacities of persons with disabilities as they not only “excel in their own fields” but make “significant contributions to the society” as well.

“With better employment prospects, persons with disabilities will be better able to lead more fulfilling and enriching lives, and contribute to their families and society”; she added.

Ms Chen receiving the award from President Halimah Yacob and Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong. On the far left is Mr Moses Lee, chairman of the Tote Board, and on the far right is Mr Edmund Koh, president of UBS Asia Pacific. Photo: Lauren Ong

In a speech, ESM Goh underscored the nation’s desire to become a more “caring and compassionate” society.

“On the occasion of the Singapore Bicentennial, I have been asking different groups of Singaporeans what kind of society they want for Singapore in SG100. Without fail, ‘caring and compassionate’ emerges among the top three choices,” he said.

The Promise Award category commends nominees for their high level of potential in talent and skills, with each awardee receiving S$5,000 in cash. The UBS Achievement Award recognises individuals who have lead extraordinary lives, in spite of their own disabilities, awarding them with S$10,000 in cash.

Ms Chen, who received a Promise Award, told TODAY: “It’s a mixture of feelings. I feel really grateful and blessed to receive the award, but feeling sad that my mum isn’t around to see it, because I know I wouldn’t be where I am without her.”

It was her late mother who introduced Ms Chen to art. When asked about what was the inspiration behind her artworks, she replied: “It was my mum’s immense, unwavering love and personal life experiences.”

And what will she do with the S$5,000? “I’ll treat my husband and my family to a superb meal, and save the rest for a rainy day.”

Coach’s use of sign language and technology helps deaf bowlers win

Extracted from the Today paper dated 13 June 2019 at

https://www.tnp.sg/sports/others/coachs-use-sign-language-and-technology-helps-deaf-bowlers-win

Coach Liew’s use of video technology and sign language helps Singapore’s deaf bowlers emerge tops at Asean championships

Jun 13, 2019 06:00 am

Bowling coach Francis Liew picked up sign language in 2009 so that he could communicate better with the deaf bowlers that he is in charge of.

Liew, 53, also writes down instructions and uses an iPad app called Video Coach, which provides video slicing and playback, for gait analysis during training.

“The common mistakes are in their swings or footwork, which will affect the last movement before their release,” he said after a training session at JForte Sportainment Centre in Kovan on Sunday.

“This way, I can tell them their mistakes, so they can see and know, and make the changes.”

His methodology, combined with the athletes’ grit, brought Singapore success at the 1st Asean Deaf Bowling Championships in Manila two months ago.

Singapore grabbed six golds, three silvers and four bronzes to emerge overall champions, ahead of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines.

Liew’s use of video technology during training was vital to their success, as playing back clips of their swings and footwork allows them to perfect minute details and build them into muscle memory.

Having a strong foundation gives the bowlers an edge during competitions, when they have to remove their hearing aids.

This makes it more challenging for them to maintain their balance and be consistent.

Women’s singles champion Kimberly Quek, 18, said: “My sense of balance is compromised. If you can stay in balance, then you can maintain accuracy and be consistent.”

The Singapore Sports School student also emphasised the importance of strengthening her core by going to the gym or running every morning.

Quek reaped the biggest medal harvest of four golds and a bronze. Her most memorable win was with doubles partner Adelia Naomi Yokoyama.

COMEBACK

Yokoyama, 20, who often gets distracted when she competes without noise, agreed.

They were trailing Filipinas Maria Catalan and Katrina Locsin throughout the event.

With one game left, they were 65 pinfalls behind. However, Yokoyama and Quek managed final games of 195 and 230 respectively to pip their opponents by six pinfalls.

Yokoyama, who was the first Singaporean Deaflympics gold medallist when she won the Masters event in 2017, clinched two golds and three silvers in the Asean meet.

Vincent Chong also pulled off an upset when he won the men’s singles event.

Chong, 51, did not expect to win as he was competing against Malaysian Mohd Firdaus, who was fifth at the 2017 Deaflympics, while Chong was 58th.

However, he maintained a steady lead to finish first, 58 pinfalls ahead of Firdaus.

“Before the competition, my coach and team manager kept hounding me to win. So, when I went to the event, I had a lot of determination to achieve that for Singapore,” said Chong, who works as a masseuse.

Chong finished with two golds and two bronzes.

Singapore Turf Club president and chief executive Chong Boo Ching said: “As part of our continuous effort to contribute back to the community, we are proud to be the sponsor of the wonderful team from Deaf Sports Association, who have not only done Singapore proud on the international stage but also inspired all of us to pursue our dreams with perseverance.”

Quek, Yokoyama and Chong will next test themselves at August’s 4th World Deaf Bowling Championships in Taiwan, where about 200 athletes from 28 countries will take part.

Patients reluctant to use hearing aids, unaware of ink between hearing loss and dementia

Extracted from the Straits Times dated 18th June 2019

SINGAPORE – Mr Doraisamy Pillay brushed off his wife’s concerns when she noticed that he had difficulty understanding her.

The school counsellor, who was then 67, chose to believe he was merely inattentive, and ignored the advice of an audiologist that he would benefit from a hearing aid.

It was only four years later, in the middle of a counselling session in 2008, that he realised he could not understand what a crying student was saying as he could not hear her.

“It was a terrible shock to me. I couldn’t help her,” said Mr Doraisamy, who was soon afterwards fitted with a hearing aid.

But his reaction is only too common in Singapore, where just 3.3 per cent of people with disabling hearing loss choose to wear a hearing aid, said senior ear nose and throat consultant at Tan Tock Seng Hospital Ho Eu Chin.

In comparison, the United Kingdom has an uptake of 38.6 per cent, and Japan, 14.1 per cent.

Almost 10 per cent of Singaporeans in their 60s suffer from disabling hearing loss, which means they have difficulty hearing conversations in a crowded coffee shop, or during a family dinner when several people are speaking, said Dr Ho on Tuesday (June 18), in an interview with the press to increase public awareness of a preventable health problem.

Related Story

Singapore study links poor vision with mental decline

Related Story

Facing dementia alone

Related Story

Fighting dementia with each step

Studies have shown that hearing loss is linked to dementia, and is in fact the most important modifiable risk factor for dementia, he said.

The reasons that link hearing loss to dementia are still being studied, but research shows as many as 25 per cent of cases of preventable dementia would benefit from treating hearing loss, he said.

His own study found that of the patients who had hearing aids fitted at the hospital between 2001 and 2013, 69 per cent were already suffering from at least moderately severe hearing loss. This is an issue of concern, he said, as it is harder to treat them.

Dr Ho also cited the National Health Survey of 2010, which found that 73.2 per cent of people with disabling hearing loss did not think they had a problem. He said people should not wait until they perceive the hearing loss themselves to seek help, and should consult a doctor once their family and friends start noticing it.

There are various reasons patients are reluctant to embrace hearing aids, one of which is that they feel it is stigmatising.

Some think that hearing aids are “very noisy”, and they should “wait until they really cannot hear” before getting one. But the issue is more complicated than that, said Dr Ho.

He explained that the complaint about noisy hearing aids has to do with how the brain perceives sound.

Human brains are naturally programmed to tune out background noises, such as traffic, or the hum of the air-conditioning.

However, as one’s hearing deteriorates, the ears no longer detect such sounds. This causes the brain to “forget” how to tune out background noise.

When patients finally get hearing aids, they are once again able to detect the sounds but have lost the ability to filter them out. This leads to the perception that hearing aids are “noisy”.

Dr Ho said this problem gets worse the longer someone who has hearing loss goes without a hearing aid, which is why one should not wait until things get “bad enough” before seeking help.

Patients are also concerned about the price of hearing aids, which cost around $3,000 on average for a pair, according to Dr Ho.

However, there are means-tested government subsidies available under the Senior’s Mobility and Enabling Fund which can greatly defray the cost.

Mr Doraisamy refused to have one because he associated it with illness, and none of his older brothers had hearing problems.

But the incident in 2008 was a wake-up call.

“That’s when I realised – if I wanted to continue working, I’d better get a hearing aid,” he said.

The hearing aid he has in each ear has “completely changed” his life for the better.

He said: “Before, I had a lot of misunderstandings with my wife as she had to raise her voice. My grandchildren would shout at me so I could hear and get scolded for being disrespectful. I didn’t want to meet friends because I was afraid I couldn’t socialise.

“But now I look forward to meeting people, I’m much more self-confident. I got my life back.”

Fellow patient Robert Nah, a 66-year-old former trader, shared his sentiments.

“People think wearing a hearing aid is inconvenient but it’s actually a solution to your problems,” he said.

Dr Ho thinks more patients would come around to wearing hearing aids if they were aware of the link between dementia and hearing loss.

He said about half of his elderly patients who were initially reluctant to get them were happy to do so after learning about the link.

He added that a “massive education effort”, both for patients and doctors, is necessary as the connection between hearing loss and dementia is still not common knowledge.

“A lot more can be done,” he said.

Harvard Law School’s first deaf-blind graduate says disability is an opportunity for innovation

Extracted from the Straits Times dated 12 May 2019

Wong Kim Hoh – Senior Writer

Haben Girma, the first deaf-blind graduate from Harvard Law School, is sitting in the living room of the US ambassador’s residence in Singapore, giving me a crash course in communication.

Nervous about committing a social faux pas, I’d used “hearing and vision-impaired” to describe her disabilities.

The disability rights lawyer says: “Hearing and vision-impaired focus on loss and limitations. They are also longer words. Blind is shorter and to the point, deaf is shorter and to the point. They also don’t have the stigmatising word: impairment. I would prefer deaf-blind.”

But she adds that the disabled community is big and diverse.

“So, there are blind people who prefer to be called legally blind or low vision or partially sighted. There’s no right or wrong way. My choice is be honest and direct and use the easiest word,” the 30-year-old adds.

Miss Girma is talking to me with the help of an interpreter who uses a keyboard to type my questions which are then transmitted to a Braille device on her lap.

She responds by speaking clearly, in full sentences pregnant with wit and humour.

“There are different types of hearing loss,” she explains. “My type is rare. I have low frequency loss and high frequency hearing. So I trained myself to speak in a higher voice, which allows me to hear some of my speech sounds.

“Throughout my life, teachers have been helping me so that I pronounce words correctly. I’ve also had public speaking courses. All of these things contribute to what you are hearing right now,” says Miss Girma, who was in Singapore recently to speak at an event organised by the Singapore Committee for UN Women.

Poised and articulate, the accomplished young woman – named by former US president Barack Obama as a White House Champion of Change a few years ago – is the third of four children of a lab technician father and a nursing aide mother.

Her mother, a refugee from Eritrea, grew up under the shadow of the Eritrean-Ethiopian War and fled by foot to Sudan in 1983 when she was 16. Her father is an Ethiopian living in California.

Miss Girma grew up in the San Francisco Bay area.

“I was lucky. The Bay Area is the heart of the disability rights movement and there were lots of activists advocating for greater change,” she says, referring to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) that prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life.

“By the time I was born, all these changes were in place. There were curb cuts on the streets which make it easier for wheelchairs to get on and off the sidewalk. By the way, physical access is good in a lot of the buildings here in Singapore, including MRT stations,” says Miss Girma, whose elder brother is also deaf-blind.

She attended mainstream public schools in Oakland.

SEIZING THE MOMENT

Always optimistic but not always practical. I wanted to travel, to try everything and to experience as much as possible.

MISS HABEN GIRMA, on living life to the fullest.

“I went to class with non-disabled students but for an hour each day, I attended a blindness programme where they taught us Braille and technology like how to travel around the Bay area by myself.

“Once a year, they would take us skiing or river rafting. The idea is that if you could take a blind kid skiing or river rafting, you are teaching them that they could do anything,” says Miss Girma, who is also an avid advocate for assistive technology for the disabled.

School was easy. What was hard were naysayers telling her parents that she was not going to achieve much in life. “They would say: ‘Oh your poor daughter. She is not going to do anything. She is never going to college, get a job or get married.’ Society creates these barriers. And my parents had to resist these negative expectations.”

Her parents had faith that she would do well and told her to work and study hard. She also had a lot of support at school.

“I’ve been successful because there were also people who said: ‘Yes, you can.’ They’d made science accessible and gym class accessible,” says Miss Girma, who went to Mali to help build a school when she was in high school.

Not that she didn’t have her share of insecurities.

Related Story

Catch up on all the life-changing stories

“Growing up, you’d get all these messages on books, TV and from the community that your life didn’t matter. I wanted to matter, so I’d try to hide my disabilities.”

She wouldn’t read a book in public because Braille books would betray the fact that she was blind.

“But doing that meant I had no access to books. So I learnt to resist societal expectations… I embraced my insecurities a little bit in high school, a little more in college and fully in law school.”

Today, she has her own definition of disability: disability means the opportunity for innovation.

She has always been an adventurous soul.

“Always optimistic but not always practical,” she says, with a smile. “I wanted to travel, to try everything and to experience as much as possible.”

With a grin, she recalls wanting to be a cowgirl when she was seven.

But until two years ago, she was always saddled with riding instructors who would hold the horse and not let her gallop, something she badly wanted to do.

“Two years ago, I had an instructor who said: ‘Of course you can gallop.’ And she let go of the horse and let me have full control,” says Miss Girma, who also loves to surf and do the salsa.

Incidentally, she stresses, deaf and blind people can be cowgirls. “You can learn to ride a horse using your voice and physical communication. There are blind people working on farms. It’s absolutely possible.”

Like her parents told her to, Miss Girma worked and studied hard. She was valedictorian of her high school and had glowing references from her teachers.

But working hard was not enough to get rid of barriers.

Although she wanted to study mathematics and computer science at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, she came up against professors who were less than helpful.

“I asked questions and one professor told me to ask someone else. It was frustrating.”

Rather than expend effort and energy constantly arguing with uncooperative professors, she decided to switch to anthropology and sociology where the lecturers and tutors were more welcoming.

“I picked my battles. It was a personal choice. I asked myself how important it was to major in computer science and maths and I decided it wasn’t that important,” she says.

Mind you, she’s no pushover.

In a speech she gave at the Perkins School For The Blind some years ago, she spoke of how she requested her school cafeteria to e-mail her the menu each day. She did not want to settle for whatever was dished out on her plate.

But the manager didn’t keep to the bargain, e-mailing her only occasionally. When she complained, he told her the cafe was busy and she should be appreciative. “I explained that Title III of the ADA requires businesses to make reasonable accommodations for persons with disabilities. If the cafeteria refused to do this, I would sue.”

That prompted not only an apology but also the dutiful daily dispatch of the menu.

Looking for a job after graduating proved just as frustrating. Her impressive resume often led to calls for interviews but landing a job was a different matter because firms couldn’t get past her disabilities.

Putting on her advocate’s hat, she says: “In the United States, 70 per cent of blind people are unemployed. And in Singapore, only 5 per cent of disabled people have employment. So a lot of hardworking, talented and brilliant people are not getting employed because employers put up barriers. We need employers all over the world to remove barriers.”

Miss Girma decided she had to do something different to get a job.

“Just getting good grades is not enough. I learnt about disability rights advocates, people who use the law to create change. And I decided to become one of them so that I can minimise discrimination against people with disabilities,” she says.

That’s how she ended up at Harvard Law School.

Her eyes widen with mock disbelief and she lets out a loud laugh when I ask, without thinking, if law school was “love at first sight”.

“What’s your excuse?” she says chidingly.

Sheepishly, I tell her she is so articulate and engaging I forget she’s deaf and blind.

Law school, she says, was not always a walk in the park. Studying contracts and legislation could be tedious and it took a while before she got to disability rights.

But her classmates were amazing. Ditto the school, which gave her unstinting support. “Harvard wanted me there and said: ‘Let’s find a way to make this work’.”

Among other things, the school provided her with materials in digitised and Braille formats, voice transliterators who narrated discussions which were fed into her earphones in class and even interpreters at networking events.

Her exam scripts were in Braille and her scripts, typed out on a computer, were graded anonymously.

“They didn’t know which was mine. Everything was very fair.”

She did well enough to earn a Skadden Fellowship, which paid her two years’ salary to do public service work.

It helped to cover her work at a non-profit law firm, Disability Rights Advocates, which files suits against employers who violate the ADA and other civil rights Acts.

She spent 21/2 years at the firm and worked on several cases. A memorable triumph was representing the National Federation of the Blind (NFB) against digital library company Scribd in 2015.

“People paid about US$9 to get unlimited access to their library but blind individuals who wanted to read books hit a wall. It was not programmed for accessibility. Scribd said the ADA did not apply to an online business,” says Miss Girma, adding that Scribd eventually settled and agreed to work with NFB to make its website more inclusive.

The lawyer has since moved on to training and speaking.

“I do presentations for companies and organisations that want to choose inclusion. It’s better to choose inclusion rather than wait to be sued. By making your business accessible and inclusive, you also reach more people,” she says, adding that there are 1.3 billion people with disabilities in the world. Collectively, they make up a market worth US$8 trillion ($10.88 trillion).

In addition to training, Miss Girma is also a speaker who has given talks all over the world. Her latest accomplishment? Authoring Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law, which is due out in August.

“On the surface, it is about my life story. But the message is about inclusion and what we can do to remove barriers out there.”

Some people, she says, might dismiss her story as exceptional.

“They will say: ‘She’s just super. Most won’t be able to do what she does’.”

But that is not true, she insists.

“The reason I’ve been able to do everything I do is that there were teachers and employers who said: ‘We believe in you and want you to contribute to our organisation and workplace.’

“My story is not the exception. There are lots of people with disabilities who are talented and brilliant. It’s up to society to remove the barriers so that they can contribute.”

Correction note: This article has been edited for accuracy.