Advisory on the Wuhan Virus Outbreak

24 January 2020 – Singapore confirms the first case of Wuhan virus, a new coronavirus that has sickened hundreds of people and killed at least 17. Here’s what you should do.

Happy Lunar New Year 2020

The Singapore Association for the Deaf (SADeaf) wishes you a happy and blessed Lunar New Year 2020. May your year be filled with abundant blessings, good health and happiness.

Blessed Lunar New Year 2020!

新加坡聋人协会祝贺大家新年快乐幸福,大吉大利。祝您新的一年,身体健康、万事如意 、合家同乐。

2020年农历新年蒙福!

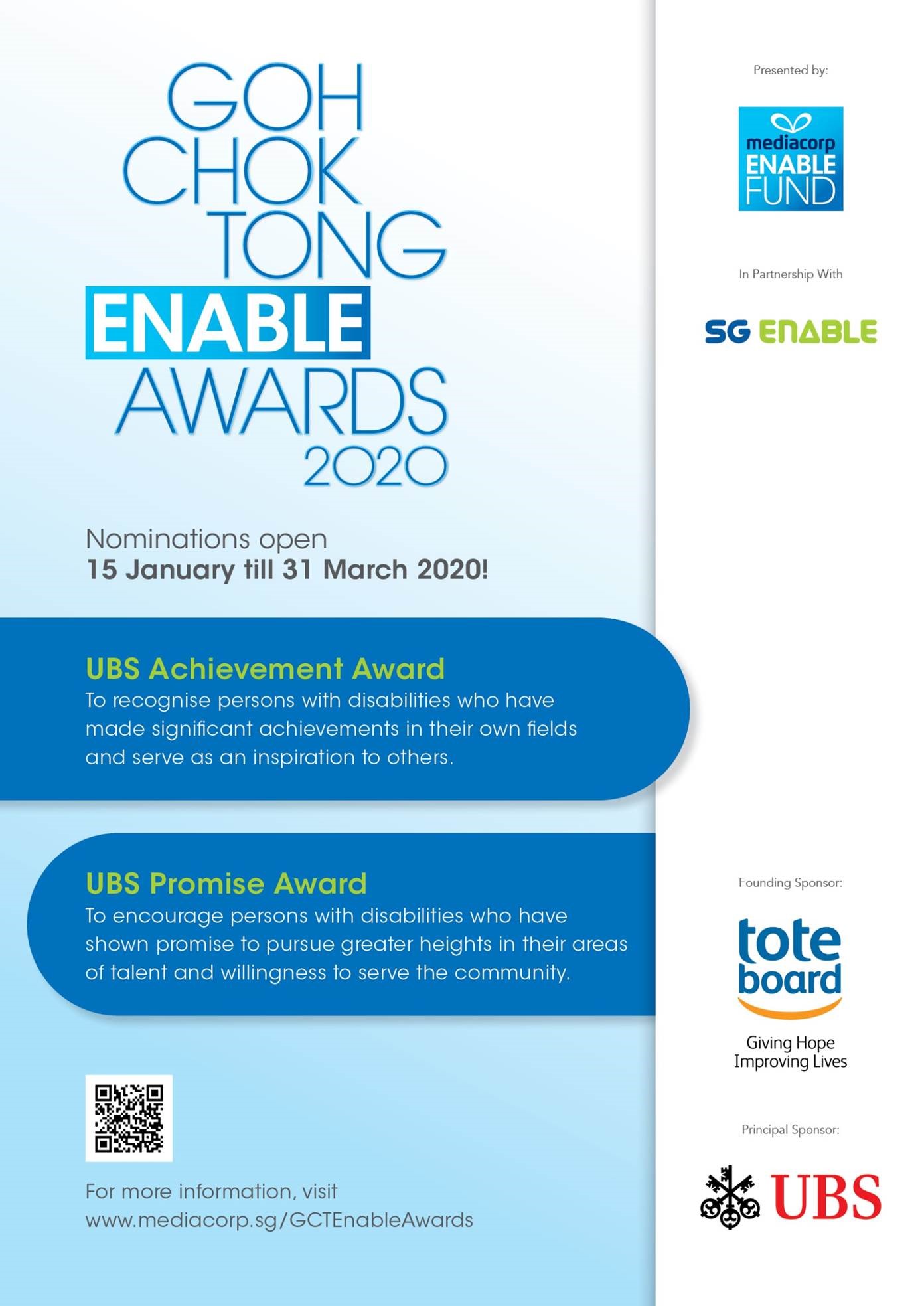

Goh Chok Tong Enable Awards 2020

GOH CHOK TONG ENABLE AWARDS 2020

Nominations now open!

Join us in celebrating the achievements and talents of persons with disabilities within our community.

Nominate someone you believe deserving of the Awards!

For more information, visit www.mediacorp.sg/GCTEnableAwards

Read more

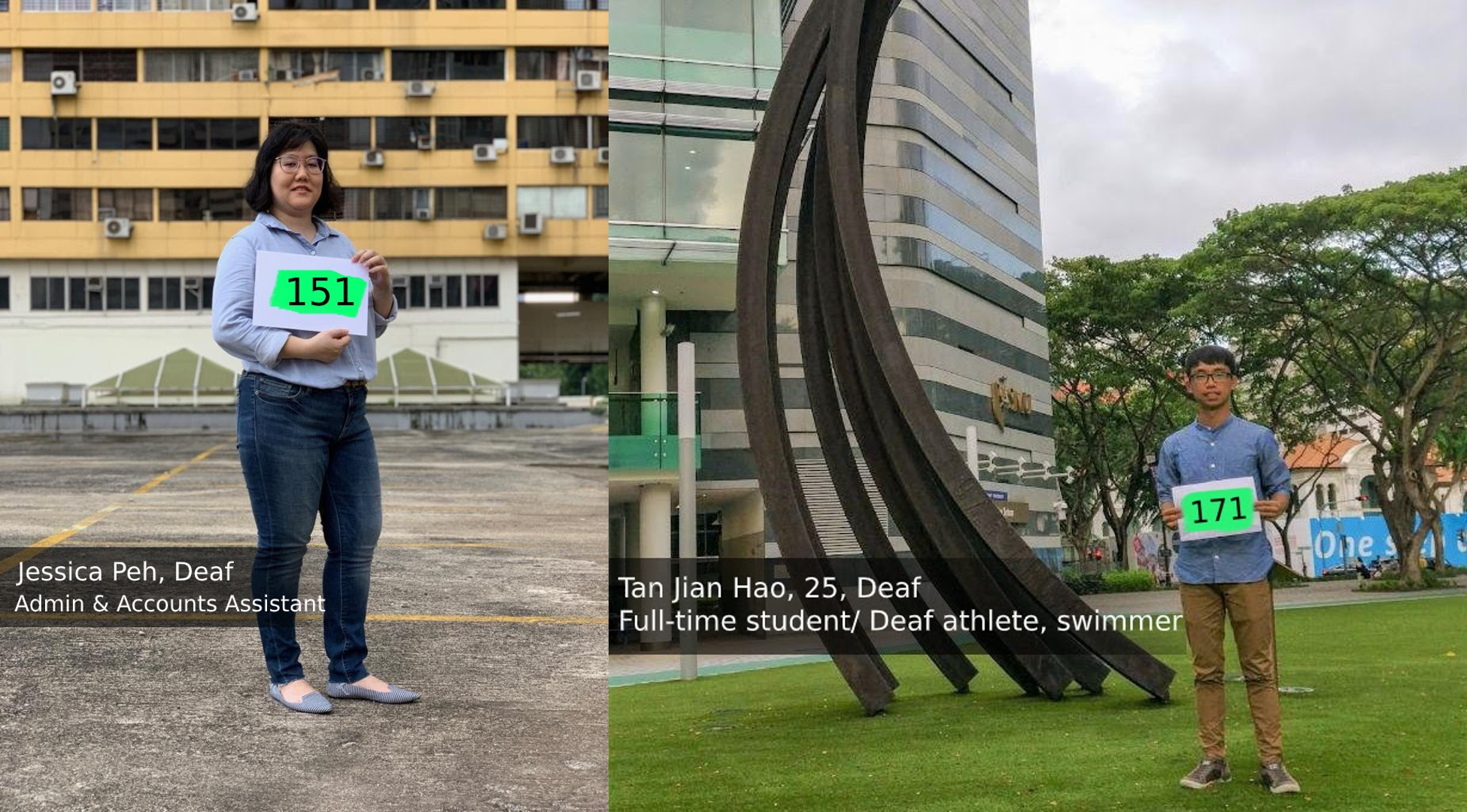

They are more than their PSLE scores

Singaporeans tend to be obsessed with good grades in school and paper qualifications. This leads to mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, among students and a rising suicide rate among youths.

A group of parents started the Life Beyond Grades initiative to shift mindsets and reduce the increasing academic pressure on our young ones by showing through examples of how grades are not everything in life. The laudable positive approach led to mainstream publicity and went viral on social media, but the campaign has yet to feature people from the Deaf and disabled groups. Here are two such stories from the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing community.

“Never give up, until you succeed”

In a school which used only oral communication, I had difficulty understanding teachers and communicating with friends. I found myself in the Normal Technical (NT) stream due to less-than-stellar PSLE results. I was also enrolled in a mainstream secondary school instead of a school which used both sign language and speech. A school that used sign language would help me better communicate with others. However, because of adults thinking they know what is best for us deaf youths, I didn’t have the power of making choices at that time.

In 2015, I enrolled in a course of my choice in Kaplan, doing a Bachelor of Science in Cyber Forensics, Information Security and Management & Business Information System. At one point, I was holding two part-time jobs because it was difficult for employers to accept a Deaf person in a full-time position. Trials like this really challenged my belief in not giving up until I succeed. Two years after graduation, I finally landed a full-time position.

I am especially grateful to my friends and mother for supporting me through my secondary, ITE, polytechnic, and university years. My classmates would explain concepts to me by writing or speaking slowly. Communicating and socialising with hearing people was a challenge for me, but these friends were kind and helpful. Thank you for being my friends.

Grades may be important, and so is having the perseverance and determination to strive hard for ourselves. But the social support from friends and family makes it so much better for us.

“Embrace the process, not just the product“

I quickly left the school upon receiving my PSLE results. I had mixed feelings. Even though I was too young to understand what my results meant, I felt paiseh. I wasn’t ashamed of myself, but I just guess that society wanted me to.

A light bulb lit up in my head during my secondary school days, and I peaked during my polytechnic years. I realised I needed to face reality and work harder than my hearing peers if I want to succeed. And I did. I managed to receive a scholarship in polytechnic, and am currently under a scholarship at university.

I wish this is a happy ending, but it isn’t. University life is challenging. I didn’t have a regular clique to depend on with because classmates change every semester. With new classmates, I had to keep repeating my story of being Deaf and my communication preferences. Given my shy personality, this was a struggle. I remembered the joy of scoring 71 marks for a quiz only to find out that I had received one of the lowest scores in class. My results were not up to expectations, and I even received a warning letter for not meeting my scholarship grade requirements. I remember getting left behind for class participation (which was graded) because it was advancing too quickly for a notetaker to catch up. I remember applying for withdrawal from school because I simply couldn’t keep up.

I’m not here to tell you a zero-to-hero story. I’ve learned that school and life is a process; there will always be ups and downs, and a single moment should not define us. I feel we should not compare ourselves with others because different people have different abilities and learning. To everyone out there, and to my younger sister, I wish to say results and failures aren’t everything. It’s about the experience and process. Even now, I’m still struggling to improve myself, and I’m sure you are too. Find something to release your worries and stress. Let’s work smart to get better each day.

Public Service Medal (Posthumous) – Mr Peng Tsu Ying

1 Dec 2019 – Dr Peng Chung Mien accepted the Public Service Medal (Posthumous) on behalf of his late father, Mr Peng Tsu Ying from President Halimah Yacob at ITE College Central.

Deaf Grab Drivers – We can do anything but hear

Mr Steven Chong and Mr Aloysius Lee shares their experience driving with Grab.

A report from World Federation of the Deaf (2009) found that out of 93 national deaf organizations around the world, 31 of them still deny Deaf people of their right to drive in their country. allow deaf people to obtain a driver’s license in their country.

Read what Grab has been doing to enable Deaf drivers here.

Click here for the Mandarin translation.

The Merdeka Stories II

One of the stories in ‘The Merdeka Stories II’ film series is inspired by Ms Barbara D’Cotta – who is the head of SADeaf’s deaf education department and has dedicated many years of service to teaching deaf students.

Read the article here: https://www.straitstimes.com/…/lifeguard-and-special-educat…

Photo credits: The Straits Times

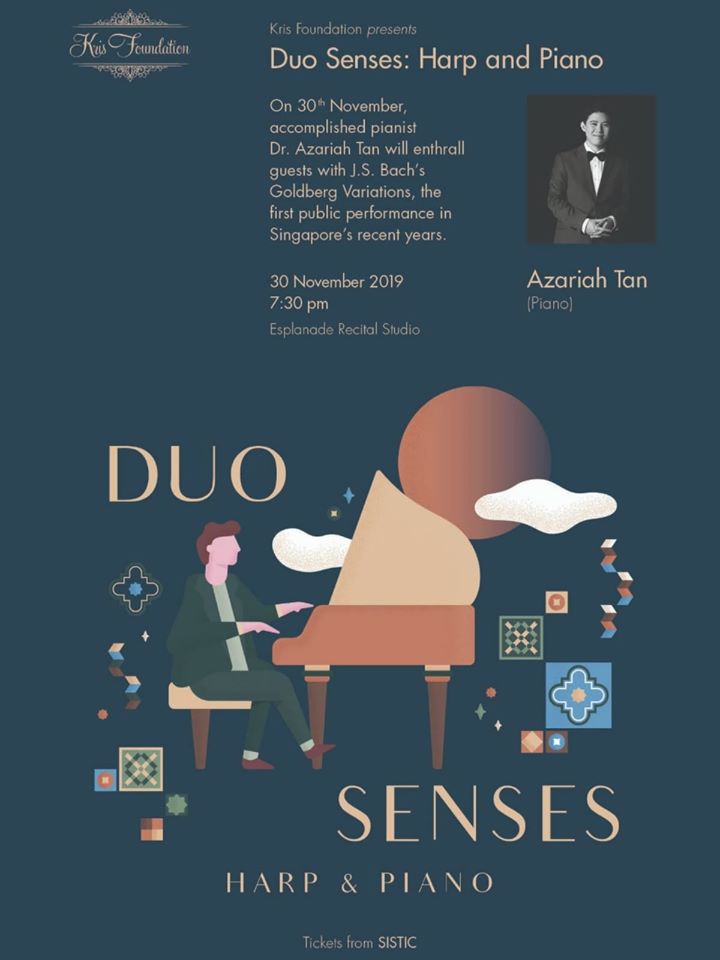

Duo Sense: Hard & Piano

Dr Azariah Tan is featured in Lianhe Zaobao & The Straits Times for his upcoming performance “Duo Sense: Harp and Piano”.

He describes the two pieces he will be performing as an experience navigating through the vicissitudes of a magnificent life and finally returning to an original peace.

Catch his enthralling performance on the 30 November, 7.30pm – 9.30pm at the Esplanade Recital Studio. For tickets: https://www.esplanade.com/events/…/duo-senses-harp-and-piano

Click here for the full article: https://www.zaobao.com.sg/zlifestyle/…/story20191126-1008307

Sweeney Todd (Sign Language Interpretation)

Staged by Singapore Repertory Theatre, Sweeney Todd will be the first sign language interpreted performance at the Sands Theatre!

There will be two access performances (Sign Language and Audio Described) on 8 Dec, 6pm. Tickets via: http://bit.ly/sweeney-todd-access

My first time attending the Purple Parade

Jason Cayanan (centre of the photo wearing a Merdeaf signboard and holding a bottle of the Purple Tea sponsored by Asia Farm), a SADeaf intern from Republic Polytechnic, details his experience attending the Purple Parade 2019 for the first time.

The Purple Parade. Sounds funky, doesn’t it? But it isn’t a dance party.

The Purple Parade is a big, big, yearly movement in Singapore, to celebrate the abilities & support the inclusion of people with special needs. This year, the event took place at Suntec City, outdoors, smack dab between Tower’s 1 & 5.

There will be a purple street parade in the proceedings, as well as the setting up of numerous purple stalls: selling toys or snacks, or challenging comers to a game of sorts.

Okay, so maybe it kind of does resemble a party. Not of dance, per se, but maybe of walking; shouting; tambourine-playing; waving about signs and banners; clapping; cheering; whistling; and (most infamously for me, at least) drumming.

Before the event, SADeaf made a video showing folks how to get to the event area, and posted it on SADeaf’s Youtube account.

Even before arriving at the venue, one could already see people in purple shirts gathering around in groups at the nearby Esplanade MRT, and within Suntec City mall itself.

And at the venue itself, it was flooded with participants. They were easily identifiable as participants, and not just people passing by, because they were all wearing purple.

Moving through the crowd was like wading through a flood at a Ribena factory. Almost everybody there wore some shade of purple. Some of them were more lilac than purple. Others were darker & newer-looking. Some of them had shades so warm that they looked almost maroon.

There were numerous stalls about, with purple name boards and fronts and sometimes even giving out purple items.

It was roughly around there that the SADeaf contingent first gathered. First, a few, then a lot. All of them wore purple, of course.

Boxes were dropped in, containing all manner of signs; banners; and sandwich boards displaying the meaning of different SgSL signs, all of them were also purple. Afterwards, we waited. People were loitering around, holding up signs, or a rod holding up a banner, or wearing sandwich boards showing all the different SgSL words like “Hurry”, “Nice”, “Okay”, “Good”, and etcetera.

And then, the parade started.

The SADeaf contingent didn’t start moving though. Instead, waiting along on an invisible timing, they let other contingents of this plum parade pass by first.

And oh, what variety!

All types of groups participated, not just those that catered to the Deaf: Health advocates carried around giant purple papier-mâché replicas of thermometers and syringes; an entire contingent of participants in wheelchairs rolled on past us, wearing masks and face paint and other stylish affectations; a contingent marching for autistic people and other special-needs people with primarily mental differences; and even contingents from big-name banks like OCBC and Citibank.

The Citibank contingent had a particularly eye-catching group decoration, with each of their members wearing a green-blue and white menagerie of twisted and tied-together balloons, their tips pointing to the sky. They all looked like a pride of colourful balloon-peacocks.

And then, it was time for SADeaf to move.

Following some invisible cue, the SADeaf contingent moved to the start point of our march. We were joined by a contingent from the Taylor & Francis Group and SADeaf’s ambassador – Grab, with them holding up their banner just a few paces behind ours.

There was a purple stage set up at the site, with two Master of Ceremonies introducing each group or company, as their contingent passed by.

The parade didn’t involve just continually walking along, though. Several times, the participants were stopped and asked to smile for the cameras. In one instance, who appeared to be a construction worker on a boom lift, asked us to smile, as he took a picture of us from an aerial perspective.

There was also another moment, where we passed near an overpass. There was a big, white sign that said “LOOK UP”, for there were people on that overpass, pausing their day to look at the participants, many of them with their phones out and aiming at them.

The Master-of-Ceremonies mentioned yet another contingent, this one composed of the students and teachers of Republic Polytechnic, Nanyang Polytechnic, and Temasek Polytechnic, all participating in the Purple Parade for the first time. I tried to crane my head, attempting to catch a glimpse of familiar faces. Alas, there seemed to have been a whole crowd of people in purple, between our contingents.

Also, the steel drumming was really, seriously loud for me. I could feel my eardrums rattling with every strike of the drum, so much so that I had to cover my ears for the rest of the march.

On a more positive note, there were lots of people cheering us on. Even if we were just walking.

As the participants walked along, our path looped rapidly. They walked from the street outside, to the road under the cover of the mall. They were heading back. And as they were walking back, a whole bunch of people offered them a merry high-five.

And then, when you start thinking the parade has only just begun, it was over.

Back at the starting point again, the participants returned all out signs and banners and sandwich boards back into the boxes they came from. For all the cheer and expense on display, one would think the route would last longer than barely over an hour, and make us go even longer than the confines of one city block. It didn’t this year, but in the future, who knows?

Click here for more photos.